November 9 - Remembering the Real History of 'Kristallnacht'

Far beyond a night of broken glass, the November pogroms were a turning point in Nazi persecution of Jewish people

The 9th of November is known across Germany as a “Schicksalstag,” a “fateful day” in the nation’s history. The first German republic was proclaimed on this day in 1918. But it is also the day of the Hitler Putsch (also known as the Beer Hall Putsch) in 1923.

It is the date the Berlin Wall came down, but the event that led to the reunification of Germany is commemorated on a different day - October 3, the day the country was officially reunited.

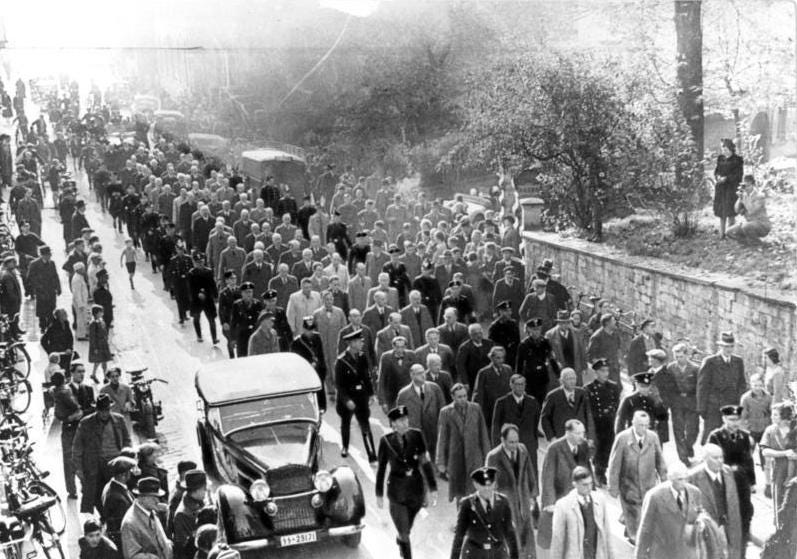

It is also the day of the November pogroms - a wave of coordinated attacks against the Jewish population that occurred all over Nazi Germany between November 9 and 10, 1938.

When I was growing up in the United States, we learned about these events by another term, “Kristallnacht.”

Translated as “The Night of Broken Glass,” we were taught it was a wave of vandalism that targeted Jewish businesses, escalating the legal and soci…