What's Left in Friedrichshain?

Despite its current reputation as a place to party, elements of the district's left-wing, working class history remain

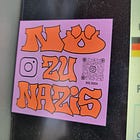

In an earlier article about the far-right demos held in our area, I mentioned Friedrichshain’s long history and reputation as a center of left-wing political and social action.

The neo-Nazis don’t choose to march here because they think they’ll see friendly faces. They do it because they know they won’t.

It’s a show of defiance and provocation - sort of demonstrating how tough they are (or aren’t), I guess.

The city district was formed in the late 19th century during the rapid industrialization of Berlin and the founding of the German Empire (this is known as the Grunderzeit in German, for “founding time/era”).

What would become the urban bezirk of Friedrichshain was an amalgamation of smaller farms, towns and suburbs that were quickly transformed into factories, warehouses, slaughterhouses, and a large port. It would also soon be home to the city’s first mu…