Back-to-School in Berlin

Over-thinking school supplies and other things

I read a blog post from another mom last week that said, ‘The new year really starts when school starts.’

I could not agree more.

I wish I could remember who said it. (If this was you, drop me a line and I will edit this post to give you credit!)

August or September, whenever my kids have gone back to school, is when I make my resolutions to be different—-and better—in the next year: Read more, meet all my deadlines, keep a cleaner house, bake all the things, be more organized.

It’s a legacy from my own childhood when each new year brought a fresh start: a new school binder, blank schedule, packs of unopened blank notebook paper.

By January, when the calendar actually changes, we will already know how much of the hopes (and how much of the fears) that we started the year with, have come to pass.

This year, I only have one kid left in school. One child to get set up with a good foundation to launch him into adulthood.

My daughter graduated from high school in the spring and is studying at a language institute and applying to different university programs. She’s not launched, yet, of course. But she’s headed in a good direction with a lot of options ahead of her—firmly in the final launch sequence.

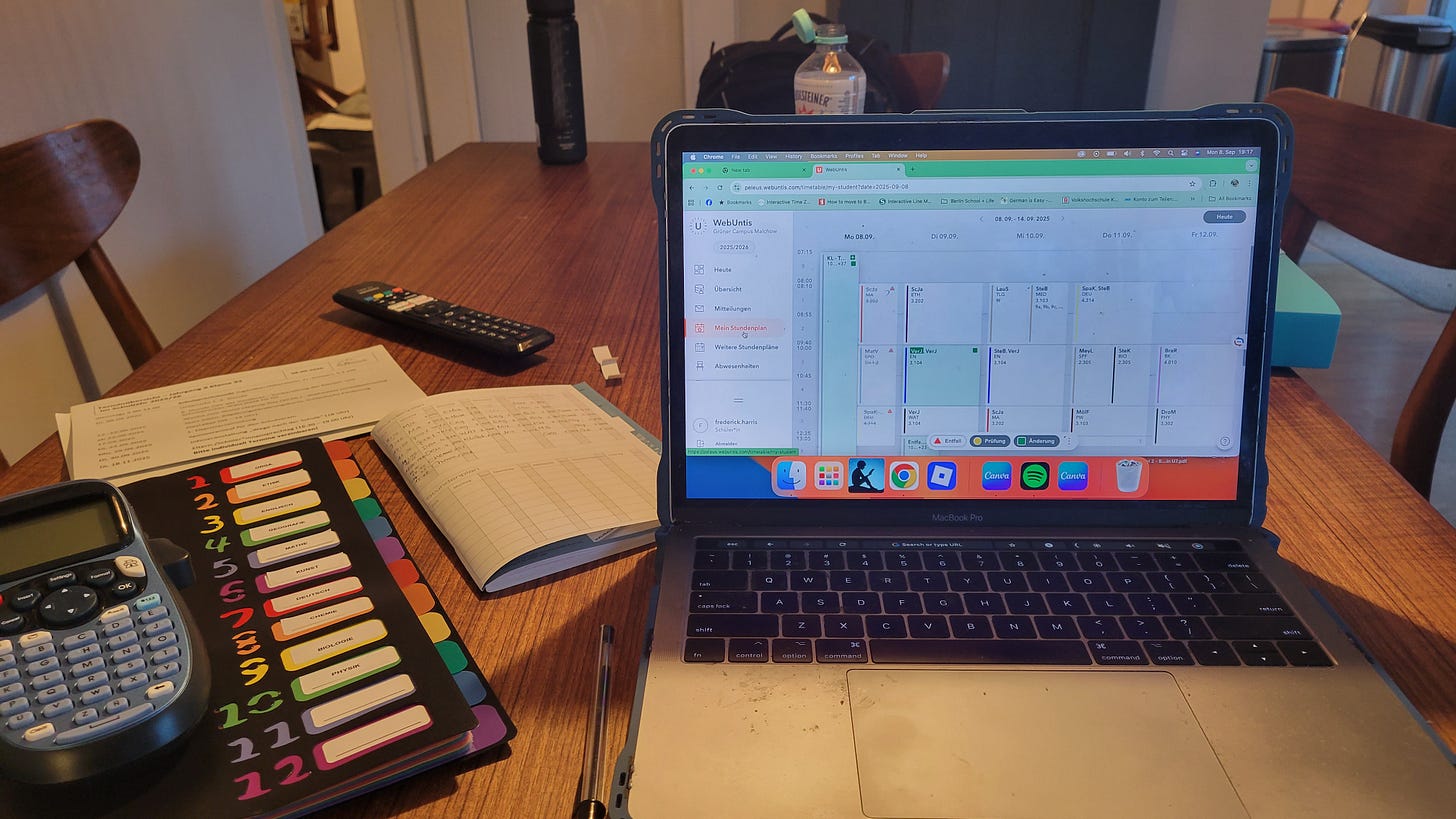

Yesterday, my son started 9th grade at a Berlin integrated secondary school (ISS). While in the States, the ninth grade is the beginning of high school, in the German system, the 9th and 10 grades are the final years of mandatory schooling.

At the end of Grade 9 (Klasse 9) the students take the tests for the Berufsbildungsreife (BBR), the first of the possible school leaving certificates.1

If they get passing grades, and are at least 16 years of age, they can leave school and look for a job or an apprenticeship.2

A quick digression …

At the end of Grade 10, Berlin students take the tests that will qualify them for the Mittlerer Schulabschluss (MSA), the certification that is equivalent to a general high school diploma in the United States and other countries.3

This is the qualification that most students who go on to do an Ausbildung must complete.

In Berlin, the ISS concept replaced two other forms of secondary schools:

the Hauptschule - vocational high schools that only offered the Hauptschulabschluss (today called the BBR); or,

the Realschule - general education high schools that offered the Realschulabschluss, a general diploma that is equivalent to today’s MSA.

The word “integrated” (integrierte in German) in the name means that the school offers all educational qualifications—the BBR, e-BBR (extended BBR), the MSA and the Abitur. Previously, only students who went to a Gymnasium after primary school were able to get the Abitur.

Berlin still has Gymnasium high schools that are exclusively focused on preparing students to get the Abitur after Grade 12. But the ISS have replaced the other “lower” types of secondary schools.

Historically, competition to get your kid a spot in a Gymnasium was fierce. These schools are seen in the popular imagination as the schools for “good” students, definitely for gifted or “high-performing” kids. They can be very selective, and they often focus on a specific area, like art or music or science or math.

Particularly among immigrant families—it’s often seen as essential for your gets to “get into” a good Gymnasium.

But it’s becoming increasingly common for many families—German and not—to choose the less-pressurized environment and slower pace of integrated schools. Your kid can still get the same Abitur, if they choose, just a year later.

(I’m planning a future article about the myths people have about the German system of tracking and separating students, as well as about what Gymnasiums are and what they aren’t.)

Controversially, the state of Berlin recently changed the terms for probationary admission to Gymnasiums, so many kids who would have been able to get a spot were no longer able to.

Ironically, this has contributed to a sort of UNO reverse for secondary school admissions—it’s now super hard to find a spot at a good ISS!

Now, back to us

As if weren’t already complicated enough, F is going to a new school this year—a different school from the ISS where he was in the “welcome class” to learn German.

(Our whole multi-pronged effort to find a new school when there is a shortage of secondary school places at almost every school in Berlin is a story in itself. But not one for today.)

So, in addition to being in high school—and in possibly the final years of high school—and studying in a language that is not his first language—he now has to again get used to a new school, new routine, and new teachers and classmates to boot.

Thus, you can probably understand why I missed last week’s Friday Wrap because I spent an hour standing in the school supply aisle at Müller debating which ballpoint pens I should purchase like my life depended on it.

It was my way of dealing with the anxiety of sending him, yet again, into a big unknown.

We opted to send him to a Berlin public school, initially, because we felt that the curriculum and methods of teaching were better suited the way he learns than the private international school that his sister attended.

We’ve asked him before if he would rather we send him to a school that teaches in English. And he always says he prefers to stay in a German school.

And the things he seems to struggle with are all issues that would exist no matter what school he attends—making friends, dealing with people you don’t like, forging your own identity and independence.

But it doesn’t mean his dad and I don’t wonder if we made the right choice.

I think every parent, when they decide to have kids, commits to a lifetime of second guessing themselves, whether they know it or not. For families living outside their home country, this can be a daily occurrence, like psychological background noise to everyday life.

I was reminded of this when I read Sourav Dey’s post about spiraling when planning the menu for his toddler son’s birthday party.

Standing in that supermarket, I realized something about the expat experience that no guidebook prepares you for. We don't just adapt to new cultures—we often over-adapt, second-guessing every decision through the lens of "Will this make us seem foreign? Will this affect how people see us?"

So, of course, I know that no amount of paper organization or finding just the right folders and pens would make this school transition painless.

But it was all I could do. (Well, that and writing the mini-dissertation about the Berlin educational system you can read in these end notes.)

For the record, he came home from his first day and gave what, for him, is a rave review:

Me: Did school go okay?

Him: Yeah. It was good.

Students at the ISSs, sometimes also called Gesamtschulen, will take the BBR. Students at a Gymnasium may not take these exams as those schools usually offer the Abitur at the end of 12th grade as their only leaving cert.

Like other educational qualifications in Germany, the BBR is not one test. It is two written exams (German and mathematics) and three oral exams (English, a science, and a social science). The MSA after Grade 10 consists of written exams in German, math, and English, plus a presentation on a topic of the student’s choice.

Students who score high enough on the MSA and have high enough grades can stay in school after 10th grade to pursue the Abitur, the colloquial term for a general university entrance qualification. (Officially, it’s the Hochschulzugangsberechtigung or HZB—you can see why it has a nickname.)

Thanks for this look at today's school system (at least in Berlin). My husband is a product of German schools, back when kids were sorted after fifth grade (!) and it was assumed that children of "academics" (= parents who went to university) or otherwise of good family went to Gymnasium. His educational experience (and mine in the US) have been no help whatsoever in navigating the Swiss school system with our son–– and that's a topic for one of my upcoming posts!

The Abitur after 12th grade is a relatively recent reform (a decade or so ago); it used to be after 13 years of school until some dunderheads decreed that "die Wirtschaft" (the economy) needs young people to be getting through their education faster. The notion backfired completely. Graduates left school with no clue about what they wanted to do next and most of them were not yet 18–– meaning they couldn't even sign an apartment lease without their parents, which is a usual step when going off to university in Germany. Suddenly Germany discovered the "gap year" concept and an entire industry catering to the needs of not-ready-for-the-next-step-Abitur-grads has sprung up since. My niece, for example, waited tables for a few months and then went to Bali to "work" as a volunteer at a sea turtle rescue station.

I do rather like the integrated school idea. My son might have done better in something like that. Good luck to your kiddo, and to you in negotiating the next transitions.

I love the ending--it sounds like you're in a complex and confusing situation on many levels, but that coming back to the present at the end is how life works if we're to stay sane. What is happening *now*, not in some imaginary future/alternative life.